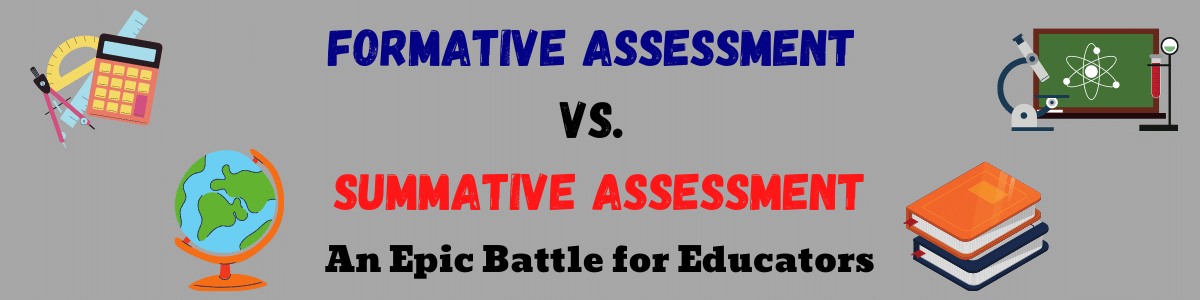

In classrooms across America, summative assessment is the reigning, undisputed champion when it comes to collecting data on what students have learned. But should this be the case? Does summative assessment do what we need it to do? Is formative assessment a smarter, stronger, faster, and/or better option? Let’s explore.

Definitions

Summative Assessment evaluates what students have learned after completion of a unit of study by comparing scores to a predetermined standard.

Formative Assessment monitors student progress during a unit of study to help educators improve their instruction, and thereby improve student learning.

The Tale of the Tape

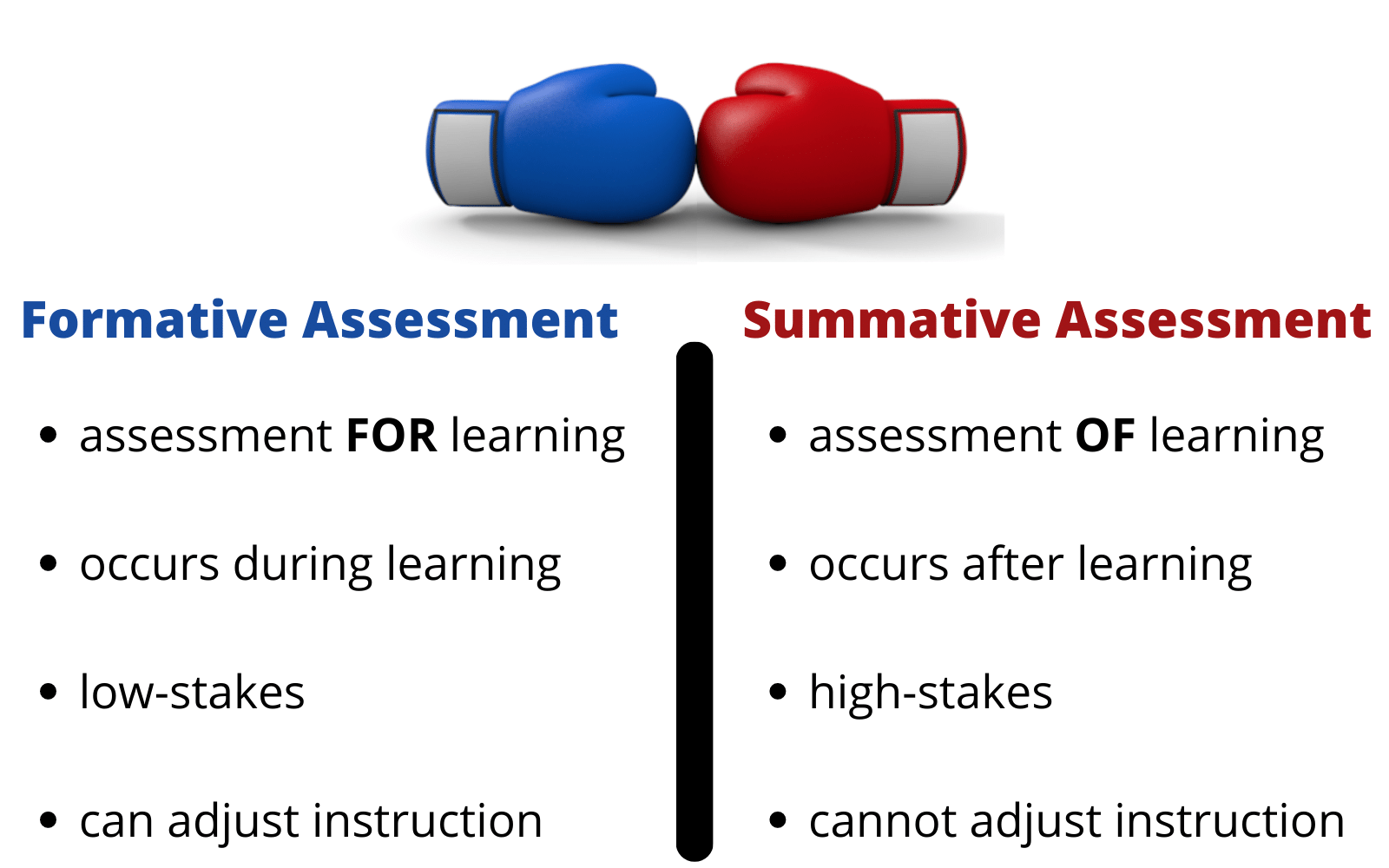

Let’s unpack the above image. Formative assessment is for learning because the intent is to improve instruction and increase learning. These assessments are done continually during the teaching/learning process and allow teachers to adjust their instruction. Summative assessment merely checks what a student has learned after a unit of study is complete. At this point, it is too late to adjust instruction.

Formative assessments are low-stakes because scores are not generated and grades are not involved. Data from these types of assessments are merely used to inform future lessons. Summative assessments are considered high-stakes because things like grades, class rankings, graduation, and college acceptance are often on the line.

Examples

Summative Assessments

- midterm or end of course exams

- cumulative projects

- End-of-unit tests

- Standardized tests such as SATs

Formative Assessments

- Whole-group opportunities to respond (including pinch cards)

- Exit tickets

- class polls

A Matter of Life or Death: A Metaphor About Assessment

Let’s say that a friend of ours has recently passed away. A doctor performs an autopsy to discover the cause of death. It is learned that our friend had a heart condition that led to his untimely death. The autopsy gave us answers, but our friend is gone and it is too late to take corrective actions.

A different friend schedules a medical appointment for an annual checkup. The doctor discovers that this friend also has a heart condition, but is able to recommend a diet and exercise regimen to help our friend improve her health. The doctor orders additional tests and schedules periodic checkups to support our friend.

The autopsy represents summative assessment. Sure, we might find out what was wrong with that friend, but he is still dead. It is too late for us to do anything about it. Summative tests are similar. A student might get a poor test score due to lack of understanding, but the unit is over and it’s time to move on to the next one. That student will probably never get a chance to update her learning.

The annual checkup is like formative assessment. The patient gets feedback in real time and the doctor can determine if different procedures might be helpful. Formative assessment not only allows teachers to give immediate feedback to students, but lets the instructor consider how to make changes to support student learning.

The Outcome

It is clear that formative assessment offers a number of advantages over summative assessment. Formative assessments can be quick, inexpensive/free, and low-pressure for the students. Many of the formative assessment strategies are engaging and can feel like games to the students. Most importantly, formative assessment allows teachers to collect real time data and make changes to teaching strategies accordingly.

To be clear, summative assessment has its place and is not going away anytime soon. Statewide testing, SATs, etc. are likely here to stay. But, as classroom teachers and administrators we can consider whether or not traditional end-of-unit tests are as valuable as we think. I would argue that we tend to rely on these tests because “that’s the way it has always been done.”

The Decision: a knockout victory for Formative Assessment!